News & Events

Stay updated with our latest news and upcoming events

Latest News

Renewable energy's trouble with 'wind theft'

As wind farms expand, some can accidentally "steal" each others' wind – causing worries over some countries' energy transition to net zero. As offshore wind farms are expanding around the world in the race to meet net zero climate targets, a worrying phenomenon is attracting growing attention: in some conditions, wind farms can "steal" each other's wind. "Wind farms produce energy, and that energy is extracted from the air. And the extraction of energy from the air comes with a reduction of the wind speed," says Peter Baas, a research scientist at Whiffle, a Dutch company specialising in renewable energy and weather forecasting. The wind is slower behind each turbine within the wind farm than in front of it, and also behind the wind farm as a whole, compared with in front of it, he explains. "This is called the wake effect." Simply put, as the spinning turbines of a wind farm take energy from the wind, they create a wake and slow the wind beyond the wind farm. This wake can stretch more than 100km (62 miles) for very large, dense offshore wind farms, under certain weather conditions. (Though more typically, the wakes extend for tens of kilometres, according to researchers). If the wind farm is built upwind of another wind farm, it can reduce the downwind producer's energy output by as much as 10% or more, studies suggest. Colloquially, the phenomenon is known as wind theft – though as Eirik Finserås, a Norwegian lawyer specialising in offshore wind energy, notes: "The term wind theft is a bit misleading because you can't steal something that can't be owned – and nobody owns the wind." Still, he points out that the phenomenon can have a number of negative consequences for wind farm developers, and even, potentially, cause problems across borders (more on this later). There are in fact a number of ongoing disputes between wind farm developers over alleged wind theft, raising concerns in countries that rely on ramping up offshore wind energy to meet their net zero climate targets. While the problem of wind theft has been long known in principle, it is growing more pressing due to the scale and speed of the offshore expansion, and the size and density of offshore wind farms, experts say. In less than five years, we need to deploy thousands more turbines – Pablo Ouro In the North Sea, which is seeing an offshore wind boom, the impact of such wakes on offshore energy production is likely to increase in the next decades as the sea becomes more crowded with wind farms, according to simulations by Baas together with researchers from the Delft University of Technology and the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. The denser and bigger the wind farm, the stronger the wake A new research project in the UK, launched this spring, aims to provide a clearer picture of the wake effect to help governments and developers improve their planning, and avoid disputes. The project will model wakes and their impact on wind farms' output in 2030, when there will be thousands more turbines in UK waters than today, says project lead Pablo Ouro, a research fellow in civil engineering at the University of Manchester. "We have seen wake effects for years, and knew they happen," says Ouro. "The problem is that in order to achieve net zero, we need to deploy a given amount of offshore wind capacity. So for 2030, we need to have three times more capacity than we have now, which means that in less than five years, we need to deploy thousands more turbines," he explains. "[Some of] these turbines are going to be operating very close to those that are already operating, so things are getting more and more crowded. So these wake effects are now starting to have more impact," he says. The UK government has pledged that by 2030, Britain will generate enough power from renewable sources, such as wind, to cover its electricity needs. A 2025 UK government policy paper highlights the need to better understand wake effects in this context, describing them as an emerging issue that creates uncertainty for offshore wind farms. Currently, there are a number of disputes in the UK between offshore wind farm developers over potential wake effects, Ouro says. In his view, these disputes are partly caused by uncertainty over the precise impact of wakes. For example, current UK guidelines on how much offshore wind farms should be spaced apart to avoid wake effects, may not reflect the actual extent the wakes can reach, he says. Also, because offshore wind farms are built in clusters, it can be difficult to assess how they might all affect each others' energy output, he explains. "When you have two wind farms, it's very simple to assess that wind farm A is interacting this much with wind farm B, and vice versa. But what if you have six wind farms, how do they interact with each other? That's what we don't know – but it's going to be happening for sure," as more and more wind farms are built, Ouro says. "The other issue is that turbines are getting very big," he notes. Turbines have been growing taller and their blades getting larger to capture more energy from the wind. The latest turbines have blades that can span more than 100m (328ft), the length of a football pitch. Among the biggest offshore turbines, a single one can power around 18,000 to 20,000 average European households. But this increase in size could worsen the wake effect since a bigger rotor diameter may create a longer wake, Ouro says, adding that more research should be done to understand the impact. Grabbing the best spots? Finserås led a study of wind wakes and regulatory gaps while undertaking doctoral research at the University of Bergen in Norway. The study analyses how the wake of a planned wind farm in Norway could negatively affect a downwind farm in Denmark. Finserås warns that unless the problem of managing wake effects is addressed, it could result in legal and political conflicts and make it harder to invest in wind energy. "The North Sea and particularly the Baltic Sea, in Europe at least, will likely be a hub for a massive-scale build-out of offshore wind farms," Finserås says. "So this issue of wake effects will very likely permeate the energy transition in the North Sea, and elsewhere." From an investment perspective, even relatively small wake effects can cause problems for offshore developers, Finserås says. "There are huge costs to building an offshore wind farm," he explains, due to the sheer scale of these farms as well as all the complex related work, including deploying special-purpose vessels. To justify their investment and make a profit, "it's very important for a developer to be able to project that the wind farm will produce a given amount of electricity for 25 or 30 years", the typical lifespan of a wind farm, he says. Even a relatively small, unexpected reduction in that energy output can upset this investment calculation and make the wind farm not financially viable, Finserås says. If operators or countries try to avoid these wake effects by securing the best spots for themselves, it can create another risk, he warns: wake effects may cause what's known as "the 'race to the water' phenomenon, whereby states rush development in order to reap benefits from the best-yet available wind resources". Rushing development could then increase the risk of ignoring other important aspects of wind farm planning, such as protecting the marine environment, he says.Ouro, at the University of Manchester, also sees a growing risk of cross-border problems: "All the disagreements that are filed to date [in the UK] are between UK wind farms, but what if tomorrow there's a dispute between a UK wind farm and a Dutch, Belgian or French wind farm? So, the sooner we anticipate this situation, and lay the groundwork for: 'Ok, that's how we're going to address this,' the better. It reduces uncertainty and is much better for the industry." Finserås recommends European countries address the problem of wind theft by cooperating and consulting with one another when planning wind farms, as well as introducing clear regulations that help manage wind as a shared resource. Essentially, wind could be treated like other shared marine resources for which there is regulation, such as oil deposits that cross state boundaries, or fish, he suggests. "It's not like [states] haven't regulated similar issues before," he says. To tackle these thorny issues, it's helpful that the European countries involved generally have good political relations, says Finserås. "We have to decarbonise energy sectors, and we have to do so very quickly, that's the ambition of the European Union when it comes to offshore wind policies," he says. "So there's no question that all of this is happening very quickly. But we shouldn't be prevented from finding good solutions just because things are happening quickly." After all, he says, it's in nobody's interest to fight over the wind. "There is an incentive to cooperate to find equitable solutions between states, despite the fact that [the wind energy expansion] is going ahead at full speed." It's not only Europe that's racing to better understand wake effects. China, for example, is rapidly expanding its offshore wind farms, and researchers there have cast a spotlight on the growing impact of wake effects on Chinese offshore wind farms. Since the project was announced in March, Ouro has been flooded with emails from people interested in it, which in his view shows just how urgent the issue is. "We need to understand this, we need to progress more on the modelling, so everyone is confident, because we need this amount of offshore wind to get to net zero. We have to deliver this." For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

Cats distinguish owner's smell from stranger's, study finds

Domestic cats can tell the difference between the smell of their owner and that of a stranger, a new study suggests. The study by Tokyo University of Agriculture found cats spent significantly longer sniffing tubes containing the odours of unknown people compared to tubes containing their owner's smell. This suggests cats can discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar humans based on their odour, the researchers say, but that it is unclear whether they can identify specific people. Cats are known to use their strong sense of smell to identify and communicate with other cats, but researchers had not yet studied whether they can also use it to distinguish between people. Previous studies of human recognition by cats have shown they are able to distinguish between voices, interpret someone's gaze to find food, and change their behaviour according to a person's emotional state that is recognised via their odour. In the study published on Wednesday, researchers presented 30 cats with plastic tubes containing either a swab containing the odour of their owner, a swab containing the odour of a person of the same sex as their owner who they had never met, or a clean swab. The swabs containing odours had been rubbed under the armpit, behind the ear, and between the toes of the owner or stranger. Cats spent significantly more time sniffing the odours of unknown people compared to those of their owner or the empty tube, suggesting they can discriminate between the smells of familiar and unfamiliar people, the researchers said. The idea of sniffing an unknown stimulus for longer has been shown before in cats - weaned kittens sniff unknown female cats for longer compared to their mothers. However, the researchers cautioned that it cannot be concluded the cats can identify specific people such as their owner. "The odour stimuli used in this study were only those of known and unknown persons," said one of the study's authors, Hidehiko Uchiyama. "Behavioural experiments in which cats are presented with multiple known-person odour stimuli would be needed, and we would need to find specific behavioural patterns in cats that appear only in response to the owner's odour." Serenella d'Ingeo, a researcher at the University of Bari who was not involved in this study but who has studied cat responses to human odours, also said the results demonstrated cats react differently to familiar and unfamiliar smells, but that conclusions couldn't be drawn over their motivations. "We don't know how the animal felt during the sniffing... We don't know for instance whether the animal was relaxed or tense," she said. Ms d'Ingeo added that the presentation of samples to cats by their own owners, who naturally added their own odour to the environment, could have increased the cats' interest in the unfamiliar ones. "In that situation, owners present not only their visual presence but also their odour," she said. "So of course if they present other odours that are different from their personal one, in a way they engage more the cat." The study's authors concluded that "cats use their olfaction [smell] for the recognition of humans". They also noted cats rubbed their faces against the tubes after sniffing - which cats do to mark their scent on something - indicating that sniffing may be an exploratory behaviour that precedes odour marking. The researchers cautioned that this relationship needs further investigation, along with the theory of whether cats can recognise a specific person from their smell.

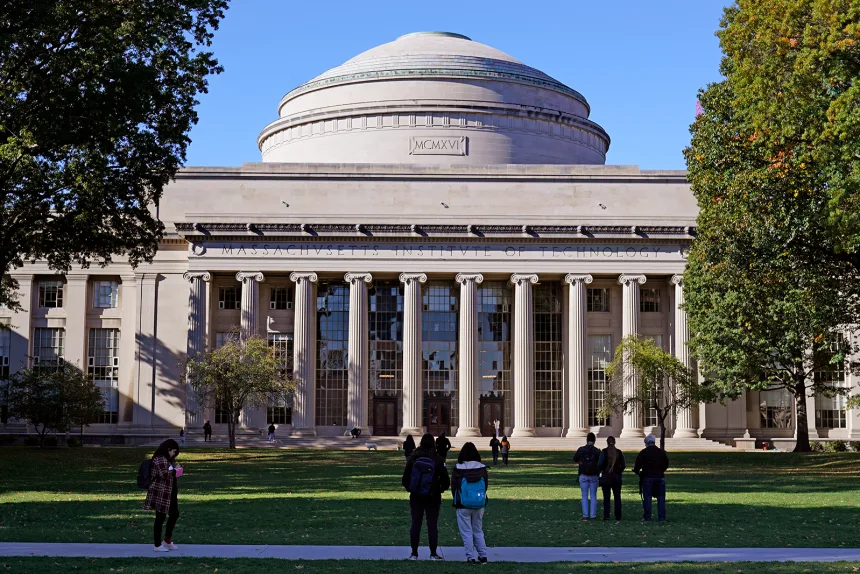

MIT is shuttering DEI office amid Trump administration’s push to end diversity programs

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has announced it will shut down its DEI office, joining a raft of universities scrambling to scale back their diversity, equity and inclusion programs amid President Donald Trump’s anti-diversity push. In a letter on its website last Thursday, MIT President Sally Kornbluth said the institution will “sunset” its Institute Community and Equity Office (ICEO) as well as a vice-president role charged with overseeing inclusion programs. Kornbluth insisted MIT is not abandoning efforts to ensure a diverse community but said the university will “shift focus to community building at the local level” and that the ICEO’s signature programs will be taken up by other departments on campus. “MIT is in the talent business. Our success depends on attracting exceptionally talented people of every background, from across the country and around the world, and making sure everyone at MIT feels welcome and supported,” Kornbluth wrote. The decision to close the DEI office follows a months-long review of the university’s diversity programs. The assessment was led by Karl Reid, the last Vice-President for Equity and Inclusion, who stepped down in February after barely one year in the job. Kornbluth’s letter did not mention the exact dates the changes are meant to take place. CNN has reached out to MIT for comments. Word of MIT’s announcement comes as the tech school’s neighbor, Harvard University, faces a consequential court hearing Thursday that may determine whether international students can attend the university or continue their studies there. The administration revoked Harvard’s certification to host international students a week ago, but a federal judge temporarily halted the move after Harvard sued the next day. Thursday’s hearing will take place just six miles from campus, where Harvard will be holding its 2025 commencement ceremony for new graduates. MIT’s undergraduate commencement is scheduled for the next day. Harvard appears to have also felt the pressure of Trump’s anti-diversity program push. Last month, the Ivy League school renamed its Office for Equity, Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging to the Community and Campus Life office. In recent weeks, universities across the country have been scrambling to comply with Trump’s anti-DEI push in the hopes of holding on to hundreds of millions of dollars in federal grants, which fund critical medical research in areas such as cancer and maternal health, among an array of scientific fields. Last month, the Trump administration threatened to cancel medical research funds and to pull the accreditation of universities that have diversity and inclusion programs or boycott Israeli companies. Just hours into his second term, Trump signed an Executive Order declaring diversity, equity and inclusion efforts discriminatory, doubling down on one of the controversial policies he pushed during his first presidency. MIT is among 45 universities targeted in an investigation launched in March by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights for “allegedly engaging in race-exclusionary practices in their graduate programs.” MIT’s decision to shutter its DEI office comes as the White House escalates its fight. This week the Trump administration moved to cancel all of Harvard’s remaining federal contracts, which total around $100 million, in addition to several billions in grants already canceled or frozen. The university is also locking legal horns with the government in a bid to unlock $2.2 billion in federal grants frozen by the administration for failing to implement its policy demands.

Upcoming Events

Don't miss out on our upcoming events and gatherings.